Nov-2019

Greatest Show on Earth: the Serengeti Wildebeest Migration

What is the migration?

What is the migration?

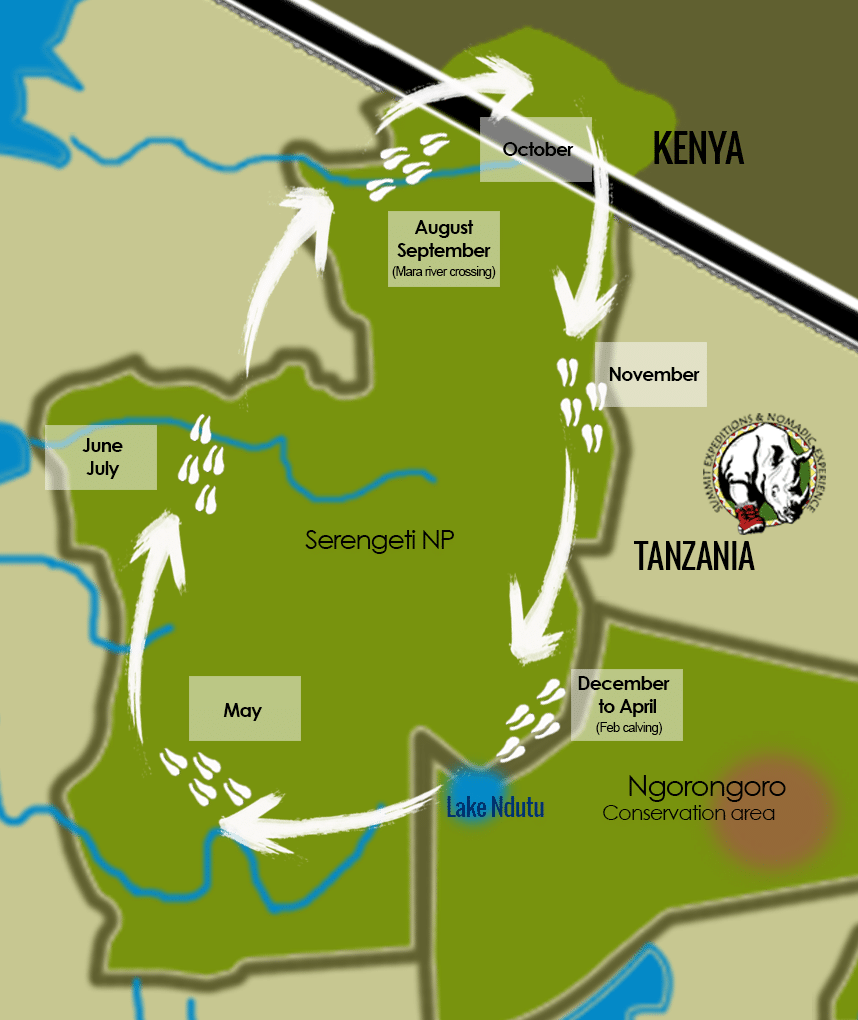

The wildebeest migration is a continuous cyclical process that occurs primarily in the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania and to a lesser extent the Masai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. One and a half million wildebeest accompanied by hundreds of thousands of zebra, gazelle, eland, and impala move in a clockwise direction over hundreds of kilometers in a constant search for green pasture and freshwater. This movement follows a more-or-less regular pattern every year.

Along the 800 kilometer route, the wildebeest encounter many dangers, including numerous predators such as lion, leopard, cheetah, hyena, and crocodile preying on the young, old, weak, and infirm; hazardous floods; the hot tropical sun; tsetse flies; and exhaustion.

The migration is considered one of the world’s most famous natural spectacles and something not to be missed by photographers and wildlife enthusiasts.

When is the best time to see the migration?

There is no one best time to see the migration, as there are always opportunities to view the immense herds, but there are better times of year to observe different aspects of the process. However, as the exact timing of the migration is dependent on the rain, it can be difficult to predict with any certainty when and where the herds will be and what they may be doing. This inconsistency is more common with the advent of global climate change. An unusually heavy or light rainfall at an unexpected time could completely alter the movement of the herds.

How does the migration proceed?

The annual migration through the Serengeti and into the Masai Mara is driven by rainfall patterns, which can vary from year to year. Therefore the movement of the herds will vary in timing and location from one year to the next. The migrating animals generally stay on the western side of the Serengeti plain as they move from south to north, and on the east side when moving north to south, but there is also plenty of zig-zag along the way, especially as large groups break off from the main herd.

As it is cyclical, there is no beginning nor ending time or place. In December to March, the wildebeest are concentrated in the southern Serengeti, where calves are born during a period of three weeks in February. Once the newborns are strong enough to walk long distances and the long rainy season has begun, the herds commence their journey northward toward more desirable fresh grasses and abundant water enabled by the rainfall.

What is the general pattern?

November: Southward movement (Loliondo and Lobo areas of the eastern Serengeti).

December to March: Calving (Ndutu area of the southern Serengeti).

April to May: Green season (southwest and central Serengeti).

June to July: Northward movement (Western Corridor of the Serengeti).

August to September: River Crossings (northern Serengeti).

October: Grazing and localized movement (northern Serengeti and Masai Mara (Kenya)).

What are the details within the general pattern?

As the short rains of November commence in northern Tanzania, the migration is drawn southward, proceeding down the eastern side of the Serengeti. They are heading for the southern grass plains around Lake Ndutu and the northern Ngorongoro Conservation Area, where they expect to find an abundance of fresh, green and highly nutritious grass to feast upon, and to feed the young once they are born.

The wildebeest and zebra stay in this area from December to March. At this time the wildebeest calving season begins. Approximately 8,000 wildebeest are born each day for about three weeks in mid-February. This time of year offers the impressive (and often disturbing) spectacle of predators waiting to pick off weak and confused calves.

As the rain spreads across the Serengeti in April, the herds will migrate north-seeking fresh grazing and water. With more abundant grazing opportunities the single large herd will split into numerous groups, with some moving farther to the west and others traveling due north. They walk through the Moru Kopjes area and west of the Seronera area (central Serengeti) in May.

The groups heading west reach the south side of the Grumeti River around June or July. Crossings of the Grumeti slow down the animals gathered in the Western Corridor. The river is composed of pools and channels which are not easy to cross, and to add to the challenge hungry crocodiles lie in wait for their annual feasting season.

In August, the herds continue moving northwards, spreading throughout the Grumeti Reserve and Ikorongo area, or further east inside Serengeti National Park proper. Here they will encounter the most serious obstacle of their journey: the Mara River. The strong currents take the weakest of the herd, predators attack the youngest, and crocodiles take animals who are seeking to cross. This creates a dramatic and unnerving spectacle of panic and confusion, but also a magnificent phenomenon for visitors who have the chance to observe the hard reality of the food chain of the Serengeti ecosystem.

In September the herds remain in the Masai Mara and far northern Serengeti, where reliable grazing exists, as the dry season intensifies through October. They will stay in the fertile Masai Mara for the duration of the dry season. They once again return southward with the advent of the November rains, preparing for another calving season.

And the cycle continues …

Facts about the migration

- In the late 1800s, a serious outbreak of rinderpest (an infectious disease of ruminants) wiped out 95 percent of the cattle in Africa and also other vulnerable wildlife, including the Serengeti wildebeest. By the 1930s there were estimated to be only 100,000 wildebeest left in the Serengeti. It wasn’t until scientists managed to eradicate rinderpest in the 1960s that wildebeest numbers began to build back up. Within 20 years, the population of wildebeest had risen to around 1.4 million and it has remained at that level ever since

- The Great Migration is the largest overland migration of mammals in the world. A similar cycle with its dramatic elements can be seen nowhere else in the world.

- The herds travel a total of 800km (500 miles) or more during each cycle.

- Every year during the journey, around 250,000 wildebeest and 30,000 zebras die from thirst, hunger, exhaustion and, of course, predators.

- Newborn calves are able to run alongside their mothers within just a few minutes after birth.

- Studies have shown that the migration phenomenon occurs without guidance, as it happens instinctively. This may explain why the herd often splits into smaller groups heading in different directions (particularly as they move northward and southward). Consequently, at times wildebeest herds can be found to be covering more than half of the Serengeti.

- Zebra and wildebeest within the herd engage in a mutually beneficial relationship. They each eat different parts of the same grasses and plants. While grazing in harmony they both keep an eye on predators and alert the other species. Furthermore, zebra are often the ones who walk onward while the wildebeest follow.

- With millions of animals moving in unison, the impact on the landscape can be significant. This impact is vital to the Serengeti’s biodiversity. The cycle of grazing enables new grass to grow and regenerate. And in addition to the higher-order predators, scavengers and birds such as vultures rely on the casualties of the wildebeest migration for their own survival.

comment this post